A new study published in the journal Nature has found that two strains of Clostridium difficile (or C. difficile) one of the most prevalent hospital-acquired infections in the U.S., might have been partly fueled by the sugar additive, Trehalose. As if we needed MORE proof that additives are bad, the results of this study have highlighted the fact that playing science with our food can and does have unintended consequences.

“C. difficile is a nasty bacterium — infection can result in severe diarrhea and death…

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly half a million people were sickened by the bug in 2011. Some 29,000 of those patients died within 30 days of being diagnosed with C. difficile, and about 15,000 of those deaths were directly linked to the infection.”1

However, given that the strength of C. difficile is relatively new, scientists are now trying to figure out how certain strains have become so virulent in the last couple of years. The first assumption, which has proven to indeed be part of the issue, is the misuse and overuse of antibiotics. But there’s more to it than just that.

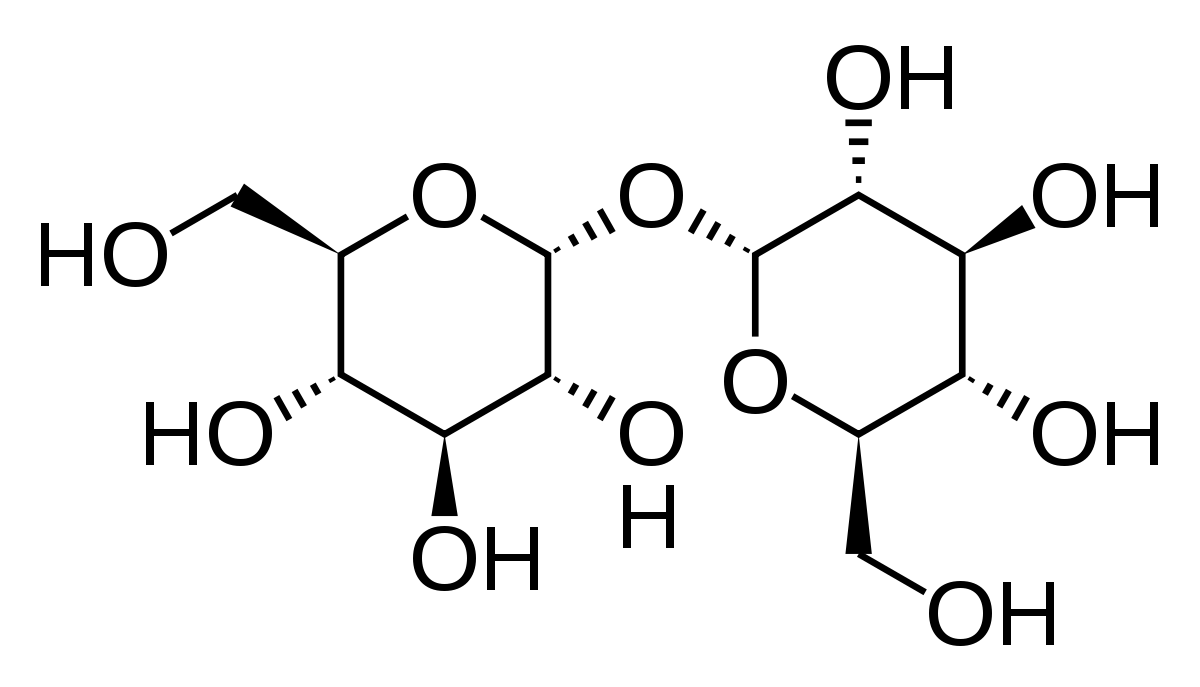

A team of scientists from Baylor College of Medicine in Texas, examined C. difficile RT027 and RT078, to see what kind of “carbon-rich molecules they ate”2 and found that both strains were able to use “low concentrations of the sugar trehalose as a sole carbon source.”3 The team analyzed RT027 and RT078 and found that while they both had RNA sequences which allowed them to snack on on trehalose in low doses, they did it very differently.

C. difficile bacteria have genes which allow them to break trehalose into glucose (a simple sugar) but the protein TreR “blocks the microbes from metabolizing trehalose unless the concentration of trehalose in the environment is very high.”4

However,

“In RT027, the TreR protein is modified in a way that lowers the bar, allowing the bacteria to metabolize trehalose even in quite low concentrations.

RT078, however, is using a different mechanism to do the same thing, having picked up four genes that are used in taking up and metabolizing trehalose. (Just one of them, it turns out, was responsible for its powered-up ability to grow in small amounts of trehalose.)”5

Researchers tested their findings in mice and discovered that when they removed a gene for trehalose metabolism in RT027 the strain became far less powerful. However, if they added trehalose to the diets of mice with an unaltered RT027 the risk of death went way up.

But not so fast. Scientists checked the RT027 bacterial load (how much of the bacteria was in their blood) and found that it was “roughly the same regardless of whether they were fed this sugar.” So, the team believes “the microbes’ improved ability to metabolize the sugar meant that they also produced more C. difficile toxins”6 and that was what made the bacteria so much more toxic.

At this point, more study is needed. But again, this study does make the case for the fact that around the same time that C. difficile started gaining strength was the same time that we started seeing trehalose used much more:

“Although considered an ideal sugar for use in the food industry, the use of trehalose in the United States and Europe was limited before 2000 owing to the high cost of production (approximately U.S. $700 per kilogram),” the authors pointed out. “The innovation of a novel enzymatic method for low-cost production from starch made it commercially viable as a food supplement (approximately U.S. $3 per kilogram).”7

Bottom line? Keep checking those labels people.