The doorbell-camera company Ring has quietly forged video-sharing partnerships with more than 400 police forces across the United States. The connection will grant police access to homeowners’ camera footage and give them a powerful role in what the company calls the nation’s “new neighborhood watch.”

Police will have a specified period to request videos recorded by homeowners. Ring says the videos will help officers see footage from millions of internet-connected cameras nationwide. The company added:

Officers don’t receive ongoing or live-video access, and homeowners can decline the requests, which Ring sends via email, thanking them for “making your neighborhood a safer place.”

RELATED STORY:

The number of police deals is likely to fuel more comprehensive questions about privacy, surveillance, and the expanding reach of tech giants and local police. The program began in 2018, and its accelerated growth has shocked some civil liberties advocates, who thought that fewer than 300 agencies had joined the partnership.

Amazon purchased Ring last year for more than $800 million, financial filings show. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post.

Ring officials and law enforcement partners describe the vast camera network as an irrepressible shield for neighborhoods. They believe it can support police investigators and protect homes from criminals, intruders and thieves. Eric Kuhn, the general manager of Neighbors, Ring’s crime-focused companion app, said:

“The mission has always been making the neighborhood safer. We’ve had a lot of success in terms of deterring crime and solving crimes that would otherwise not be solved as quickly.”

RELATED STORY:

Nevertheless, privacy advocates and legal experts have expressed concern about the company’s eyes everywhere ambitions, and its increasingly close relationship with police. They say the program could threaten civil liberties, turn residents into informants, and put innocent people, including those who Ring users have flagged as “suspicious,”at risk to greater surveillance.

According to Andrew Guthrie Ferguson, author of “The Rise of Big Data Policing” and law professor:

“If the police demanded every citizen put a camera at their door and give officers access to it, we might all recoil. By tapping into “a perceived need for more self-surveillance and by playing on consumer fears about crime and security,” Ring has found “a clever workaround for the development of a wholly new surveillance network, without the kind of scrutiny that would happen if it was coming from the police or government.”

RELATED STORY:

Ring has grown into one of the nation’s biggest household names in home security. The company, based in Santa Monica, Calif., sells a line of alarm systems, floodlight cameras and motion-detecting doorbell cameras starting at $99, as well as monthly “Ring Protect” subscriptions that allow homeowners to save the videos or have their systems professionally monitored around the clock. Here is a rundown of how Ring works, according to the Washington Post:

Ring users are alerted when the doorbell chimes or the camera senses motion, and they can view their camera’s live feed from afar using a mobile app. Users also have the option of sharing footage to Ring’s public social network, Neighbors, which allows people to report local crimes, discuss suspicious events and share videos from their Ring cameras, cellphones and other devices.

The Neighbors feed operates like an endless stream of local suspicion, combining official police reports compiled by Neighbors’ “News Team” with what Ring calls “hyperlocal” posts from nearby homeowners reporting stolen packages, mysterious noises, questionable visitors and missing cats. About a third of Neighbors posts are for “suspicious activity” or “unknown visitors,” the company said. (About a quarter of posts are crime-related; a fifth are for lost pets.)

Users, which the company calls “neighbors,” are anonymous on the app, but the public video does not obscure faces or voices from anyone caught on camera. Participating police officers can chat directly with users on the Neighbors feed and get alerts when a homeowner posts a message from inside their watched jurisdiction. The Neighbors app also alerts users when a new police force partners up, saying, “Your Ring Neighborhood just got a whole lot stronger.”

To seek out Ring video that has not been publicly shared, officers can use a special “Neighbors Portal” map interface to designate a time range and local area, up to half a square mile wide, and get Ring to send an automated email to all users within that range, alongside a case number and message from police.

The user can click to share their Ring videos, review them before sharing, decline or, at the bottom of the email, unsubscribe from future footage-sharing requests. “If you would like to take direct action to make your neighborhood safer, this is a great opportunity,” an email supplied by Ring states.

RELATED STORY:

Ring said it would not provide user video footage in response to a subpoena. But added it would cooperate if company officials were served a search warrant or felt they had a legal obligation to provide the content. Its terms of service state:

“Ring does not disclose customer information in response to government demands unless we’re required to do so to comply with a legally valid and binding order,” the company said in a statement.

Ring users consent to the company giving recorded video to “law enforcement authorities, government officials and/or third parties” if the company thinks it’s necessary to comply with “legal process or reasonable government request.”

The company says it can also store footage deleted by the user to comply with legal obligations.

RELATED STORY:

Not only do the high-resolution cameras can give detailed images of a front doorstep, but they also capture neighboring homes across the street and down the block. Ring users have expanded their home monitoring by installing the motion-detecting cameras along driveways, decks and rooftops. According to the Washington Post:

Ring users have shared videos of package thieves, burglars and carjackers in the hope of naming and shaming the perpetrators, but they’ve also done so for people — possibly salespeople, petitioners or strangers in need of help — who knock on the door and leave without incident. (Other recorded visitors include lizards, deer, mantises, snakes and snooping raccoons.)

Ring users’ ability to report people as suspicious has been criticized for its potential to contribute to racial profiling and heightened community distrust. Last Halloween in southern Maryland, a Ring user living near a middle school posted a video of two boys ringing their doorbell with the title: “Early trick or treat, or are they up to no good?”

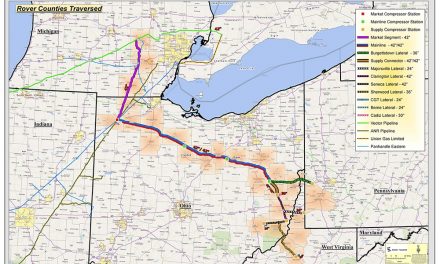

Since officially launching its Neighbors police partnerships with officers in March 2018, Ring has extended the program to 405 sheriff’s offices and police departments across the country.

Ring has aggressively pursued new police alliances. The company has urged police to encourage homeowners to use Neighbors. Ring has offered discounts to cities and community groups that spend public or taxpayer-supported money on the cameras. The firm also has given free cameras to police departments that can be distributed to local homeowners. The company said it began phasing out the giveaway program for new partners earlier this year.

RELATED STORY:

For months, Ring has tried to keep key details of its police-partnership program private. But public records from agencies nationwide have revealed snippets of the company’s close work with local police. Ring says it offers training and education materials to its police partners so they can accurately represent the service’s work.

Ring’s expansion has led some to question its plans. The company applied for a facial-recognition patent last year that could alert when a person designated as “suspicious” was caught on camera. The cameras do not currently use facial-recognition software, and a spokeswoman said the application was designed only to explore future possibilities.

Amazon, Ring’s parent company, has already developed facial-recognition software, called Rekognition, that is used by police nationwide. The technology is continuously improving. Earlier this month, Amazon’s Web Services arm announced that its face scanning system could even track the emotion of FEAR.

Source:

Please get on our update list today, as social media is strangling our reach. Join here: http://healthnutnews.com/join THANK YOU!