Last week, the U.S. government demanded genetic data from Ancestry.com, creating anxiety around the different types of access police have to DNA data.

But that’s not the only thing that should concern Americans. They should also take note of the government’s secretive plundering of citizens’ most private data contained in their medical histories, which is mostly going unnoticed.

According to Forbes, it appears police raids on medical tech companies may be more frequent and more fruitful than those on places like Ancestry.

RELATED STORY:

Electronic medical records fail again, as 12 million patient records at Quest Diagnostics get hacked

You might be wondering who the government is getting this medical data from? Thomas Brewster of Forbes remarked:

I’ve found multiple cases where federal agents have been quietly rummaging through databases of American citizens’ medical histories.

They’re doing so via little-known healthcare tech companies. According to court files I reviewed, the government has found at least one new possible reservoir of medical information: a 10-year-old, successful Sunnyvale, California, startup called DrChrono.

It’s worth close to $50 million, according to Pitchbook, and just last month raised $20 million. DrChrono’s aims to make electronic health records easier for doctors and their practices to manage, placing everything from patient histories and billing information in one place in the cloud. It claims its software manages data on around 17.8 million patients and processed more than $11 billion in medical bills to date.

Sounds useful for the doctors, but it’s also useful for police when they’re investigating a crime in which they want to access medical records. The search warrants I discovered show that when cops come knocking with a valid legal request, DrChrono is happy to hand over data. Lots of data.1

RELATED STORY:

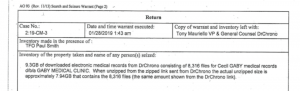

In fact, January of last year, DrChrono gave 9.3GB of medical records (8,316 files) from the Gaby Medical Clinic in Fort Smith, Arkansas.

A screenshot of a search warrant document shows DrChrono providing more than 8,000 files of medical records to the U.S. government. Forbes Media

In that circumstance, the Drug Enforcement Administration was investigating two doctors—Donald Hinderliter and Cecil Gaby—over allegations they were distributing large amounts of powerful drugs like Oxycodone and Xanax. Witnesses had informed the DEA that some patients had suffered fatal overdoses. (Both Hinderliter and Gaby have pleaded guilty to charges of distributing controlled substances and are awaiting sentencing).1

In July 2019, in a completely separate case, DrChrono furnished the government with records related to the Pennsylvania-based practice of Neil Anand, who was under investigation for giving out “goody bags” of drugs to patients who didn’t need or ask for them.

RELATED STORY:

In a search warrant uncovered by Brewster, the investigating agent goes into little detail about what exactly he was able to determine from DrChrono records, stating:

“I am aware that the medical records contained entries from DrChrono with notes for office visits on September 9, 2018 and July 23, 2018 indicating that Former Employee 2 was Patient 4′ s medical provider on these dates.”1

Even appointment notes are included in the files. Again, that’s especially sensitive and revealing data. And in this case, it appears the government has obtained data belonging to at least one victim, not a suspect.

Dr. Deborah Peel, founder, and president for Patient Privacy Rights, says companies like DrChrono can and will aggregate and sell your data. She warns:

“The data holders now control our health data.”1

In reviewing DrChrono’s privacy policy, indeed, it reserves some rights to sell users’ information. A closer look indicated it does reserve the right to sell data to affiliated companies, or to anyone for non-direct marketing purposes, stating:

“We do not rent, sell or share personal information about you with other people or non-affiliated companies for their direct marketing purposes, unless we have your permission.”

“We are not responsible for the privacy practices of the others who will view and use the information you disclose to others.”1

It appears that investigations using DrChrono data appear to be continuous. According to Brewster:

I put in a freedom of information request with the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General, asking it for any communications it had with DrChrono. That agency is notable for being the largest inspector general’s office in the federal government and it’s playing a major role in the fight against opioid epidemic. The agency said it couldn’t provide records, but it noted: “This office has been informed that there is an open and ongoing investigation concerning the subject of your request.”

I found just a small number of requests for medical records for DrChrono and similar businesses. But it’s possible, even likely, there are others and DrChrono’s competitors are most likely being asked to hand over people’s health data too. I discovered one other case where the government wanted to search an account at rival Practice Fusion, though the case files were sealed.1

RELATED STORY:

According to Brewster, Americans should be more concerned about why the government’s looking into your healthcare history than it is your DNA data. As Dr. Peel puts it:

“We have no right to health privacy, no right to control our health data in the US.”1

Brewster points out that we should all be concerned about our privacy, stating:

First, Ancestry only received one demand for genetics data in 2019 (one which it rebuffed), compared to the two that I found for DrChrono.

Second, unlike Ancestry, the likes of DrChrono don’t have transparency reports that inform people how often governments are telling them to reveal data.

And not only do they have masses of super-sensitive data, these small businesses don’t have the same financial clout to fight broad, invasive government orders as much larger tech companies.

Whilst federal investigators are legitimately looking into serious crimes, ones that contribute to America’s severe opioid crisis, it appears the victims of that particular menace are, perversely, having their privacy invaded alongside pill pushers.1

Neither DrChrono nor its CEO Michael Nusimow had responded to multiple requests for comment.