Geoengineering: Opportunity or folly?

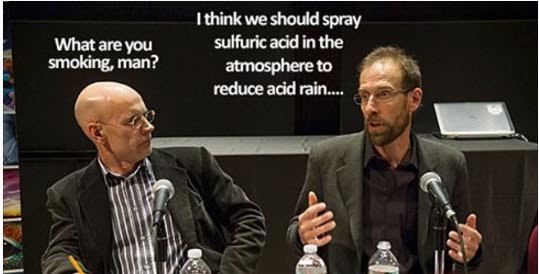

Professors Keith & Hamilton differ sharply on climate change proposal

The technology to shield Earth from sunrays and cut the ‘Harmful warming” expected in the coming decades is so cheap and readily available that the hurdles to doing it are social, not technical, says Harvard’s David Keith, a supporter of geoengineering.

Opponents say the idea would not only drain energy from efforts to address climate change’s causes, but also is loaded with unknown risks and the potential for abuse.

The early debate over geoengineering as a solution to our accelerating climate problem was aired Monday at the Science Center. In an event co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment and the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change the authors of books taking opposing sides made their cases, one offering a scenario in which technology blunts the very worst of warming and buys time for other efforts to take hold, the other describing a future where the root causes of warming are ignored while weather is controlled by corporations or governments far removed from the effects.

Keith, the Gordon McKay Professor of Applied Physics in the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and professor of public policy at the Kennedy School, published “A Case for Climate Engineering” in September. Arguing against research efforts in geoengineering was Clive Hamilton, a professor of public ethics at Charles Sturt University in Australia and author of “Earthmasters: The Dawn of the Age of Climate Engineering,” published in February. Steven Barrett, an assistant professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT, moderated the discussion.

Keith started by arguing that the time to begin research into geoengineering is now, so that science will have a chance to learn about potential pitfalls before the worst of warming hits.

Though “geoengineering” encompasses several approaches to addressing the climate problem, Monday’s debate focused on the spraying of sulfate aerosols high in the atmosphere, a relatively inexpensive option and the one likeliest to be deployed on a large scale. The effect would mimic the global cooling power of large volcanic eruptions, which send similar chemicals into the atmosphere. The particles reflect sunrays and have been known to cause unusually cool weather — “volcanic winters” — for months or even years afterward.

The effects of those winters are potentially severe. The 1991 explosion of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines cooled global temperatures for several years, while the 1883 explosion of Krakatoa, in Indonesia, triggered record snowfall and harsh winters.

The geoengineering scenario envisioned by Keith is far less dramatic. He suggested gradually ramping up sulfate releases for 50 years starting in 2020 with the aim of reducing warming from climate change by half. Around 2070, with other mitigation strategies yielding results, the program would begin winding down.

At maximum, Keith said, the plan would release a million tons of sulfates into the atmosphere, about an eighth of what Mount Pinatubo released. The process would be cheap and remarkably straightforward, he said. It could be accomplished with modified versions of today’s aircraft.

“All the hard problems are essentially social,” he said.

Among the plan’s strengths, Keith said, is that it addresses the lag between cutting carbon emissions and the removal of carbon from the atmosphere by natural processes.

Though the techniques involved in geoengineering have been known for some time, the issue has been taboo, Keith said, because of worries that it might discourage work on the underlying causes of climate change. Now is the time, he said, to lift the taboo and initiate a research program — publicly funded to minimize corporate influence, and collaborative to incorporate diverse views.

Hamilton countered: Regardless of the intent of research, it would draw commercial interests. Once established, those interests would lobby to use the technology that was developed. Researchers on the project would also be a concern, he said, drawing comparisons to the scientists who gave the world nuclear weapons in World War II. Some spent the rest of their lives trying to control what they helped create; others continued to support the development of nuclear bombs as a route to gaining power and influence.

“Which paths will geoengineering advocates take?” Hamilton asked.

Even if governments could keep control over the technology, Hamilton said, the deployment of geoengineering — with the potential to trigger droughts and flooding — would lead to the troubling issue of climate being controlled remotely, with scant concern for on-the-ground consequences.

Also, Hamilton said, the claims around geoengineering make it attractive to opponents of the painful measures needed to cut carbon dioxide emissions, including fossil-fuel giants such as Exxon Mobil and Royal Dutch Shell. He pointed out that N. Murray Edwards, the billionaire mogul mining Canada’s oil sands, recently invested in Keith’s geoengineering startup, Carbon Engineering.

These issues, said Hamilton, all but guarantee that geoengineering-based solutions to climate change would not be guided by the best intentions and research. Rather, they would be intensely political, with powerful interests supporting development and deployment in order to protect business in fossil fuels.

Keith said there is nothing sinister about Edwards investing in his company, which he sees as Edwards “hedging his bets” in the climate debate, in case fossil fuels prove a bad investment. He acknowledged that the technology might be attractive to a fossil fuel company, but said he doesn’t think the technology alone would generate a lot of commercial interest, because it would generate little profit yet carry high risk.

“There are many cases where we can do a good job of limiting environmental impacts by manipulation [of the environment], and cases where we’ve done that already. The most grandiose [way to describe it] would be to say this is a version of restoration ecology on a planetary scale,” Keith said.