Dr. Yu-Han Chiu, a research fellow in the department of nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and first author of the study said:

The study looked at 325 women between the ages of 18 and 45 who were undergoing infertility treatment with assisted reproductive technology at Massachusetts General Hospital. Researchers had them complete a diet assessment questionnaire, took their height and weight and measured their overall health (researchers made sure to account for factors that could influence the study such as supplements and residential history).

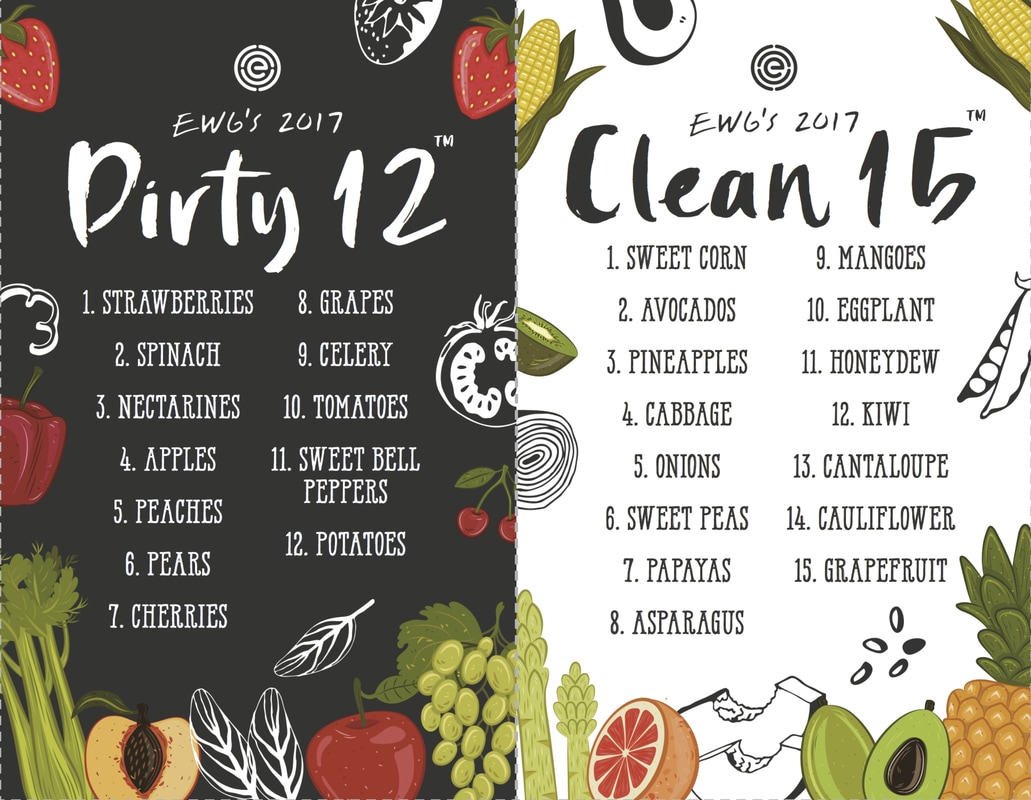

The team then “analyzed each woman’s pesticide exposure by determining whether the fruits and vegetables she consumed had high or low levels of pesticide residues, based on reports from the US Department of Agriculture’s Pesticide Data Program, which monitors the presence of pesticides in foods sold throughout the United States.”

What researchers found was that compared to women who ate less than one daily serving of high-pesticide-residue fruits and veggies, those who ate 2.3 servings or more had an 18% lower probability of getting pregnant and 26% lower probability of giving birth to a live baby.

Now, given that the women in the study were trying to become pregnant via infertility treatments and because they self-reported info about their diets (self-reporting can be inaccurate) more research is needed.

However, Dr. Philip Landrigan, the dean for global health and professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, wrote an editorial that accompanied the study and said:

“…the observations made in this study send a warning that our current laissez-faire attitude toward the regulation of pesticides is failing us. We can no longer afford to assume that new pesticides are harmless until they are definitively proven to cause injury to human health. We need to overcome the strident objections of the pesticide manufacturing industry, recognize the hidden costs of deregulation, and strengthen requirements for both premarket testing of new pesticides, as well as postmarketing surveillance of exposed populations — exactly as we do for another class of potent, biologically active molecules — drugs.”