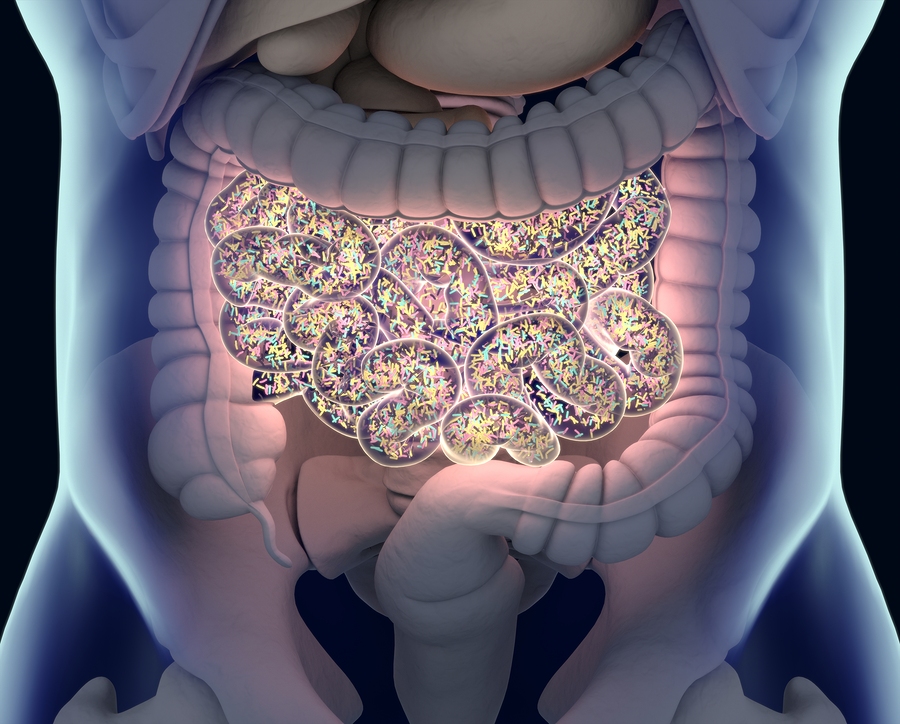

The human gut has “a diverse collection of microorganisms making up some 1,000 species, with each individual presenting with their own unique collection of species.” But it wasn’t known whether this variation is on a continuum or if people cluster into specific classifiable types until a famous study analyzed the gut flora of people across multiple countries and continents. The researchers identified three so-called enterotypes. It’s pretty amazing that with so many hundreds of types of bacteria that people would settle into just one of three categories. The researchers figured that our guts are like ecosystems, similar to how there are a lot of different species of animals on the planet, but they aren’t randomly distributed. You don’t find dolphins in the desert, for example. Instead, in the desert, you find desert species, and, in the jungle, you find jungle species because each ecosystem has different selective pressures, like rainfall or temperature. This study suggested there are three types of colon ecosystems so you can split humanity into three types: people whose guts grow out a lot of Bacteroides-type bacteria, those whose guts are better homes for Prevotella, and others who foster the growth of Ruminococcus.

RELATED STORY:

If you think it’s amazing that researchers were able to boil it down to fit everyone into one of just three groups, subsequent research on a much larger sample of people was able to fold Ruminococcus into Bacteroides, so now everyone seems to fit into one of just two groups. So, now we know, when it comes to gut flora, there are just two types of people in the world: those who grow out mostly Bacteroides and those who overwhelmingly are home to Prevotella species.

The question is why? It doesn’t seem to matter where you live, whether you are male or female, or how old or skinny you are. What matters is what you eat. Researchers looked at more than 100 different food components, and a theme started to arise. Different groupings of bacteria were associated with the presence of a particular food component in the diet. In my video What’s Your Gut Microbiome Enterotype?, you can see this illustrated in what’s called a heat map. Each column of the heat map is a different grouping of bacteria, and each row is a food component. Red is like hot, meaning a close correlation between the presence of a particular bacteria and lots of a particular nutrient in the diet. Blue is like cold, meaning you’re way off—a reverse correlation, meaning lots of a nutrient is correlated with very low levels of a bacteria in our gut. Bacteroidesand Prevotella are kind of opposites. When it comes to things like animal fat, cholesterol, and animal protein, Bacteroides is red and Prevotella is blue, but when it comes to plant components like carbohydrates, Prevotella is red and Bacteroides is blue.

RELATED STORY:

The study results clearly showed that the components found more in animal foods are associated with the Bacteroides enterotype, while those found almost exclusively in plant foods are associated with Prevotella. So, it is no surprise that another study found that African Americans fell into the Bacteroides enterotype, whereas most of the native Africans were Prevotella. This may matter because the Bacteroides species generally are associated with increased risk of colon cancer, our second leading cause of cancer death, yet a disease almost unheard of among native Africans. The differences in our gut flora may help explain why Americans appear to have more than 50 times the rate of colon cancer.

RELATED STORY

If whichever gut flora enterotype we are could play an important role in our risk of developing chronic diet-associated diseases, the next question is whether we can alter our gut microbome by altering our diet. The answer? Yes. Diet can rapidly and reproducibly alter the bacteria in our gut. Learn more in my video How to Change Your Enterotype.

In health,

Michael Greger, M.D.

*Article originally appeared at Nutrition Facts.